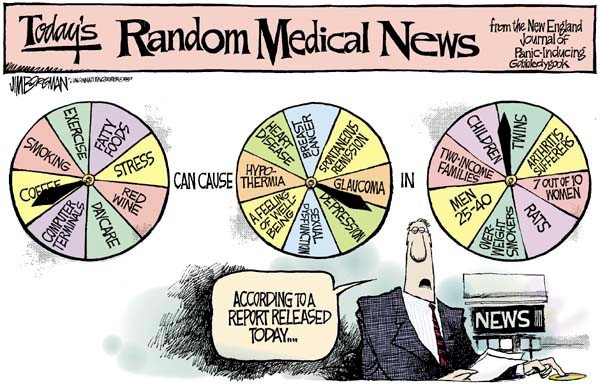

Earlier this summer, the popular science and technology blog io9 ran a story that caught the eyes of many: I Fooled Millions into Thinking Chocolate Helps Weight Loss. Over the course of the article, John Bohannan, a science journalist, describes his elaborate hoax and laments the state of both nutrition research and science reporting. Unfortunately, this is all too common.

Although the study was real, it was intentionally plagued by methodological and analytical flaws, including an extremely small sample size and large number of measurements that gave the study a greater than 60 percent chance of finding at least one statistically significant result. To address these issues, some journals are considering getting rid of p-values (a measure indicating how likely it is that study results are due to chance) and many do not accept studies with fewer than 30 subjects. Nevertheless, many low quality studies still end up published in peer-reviewed journals.

Nutrition research is particularly vulnerable to biased results because of its dependence on self-reporting. A recent Mayo Clinic Proceedings article argued that memory-based dietary assessment methods were fundamentally and fatally flawed and should not be used to inform dietary guidelines. Organizations like the Nutrition Science Initiative are trying to combat these issues by funding more rigorous (and expensive) studies. While the evidence is inconclusive for some nutrition research questions, the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee seems to be a step in the right direction with its emphasis on minimally processed wholesome foods rather than specific nutrients.

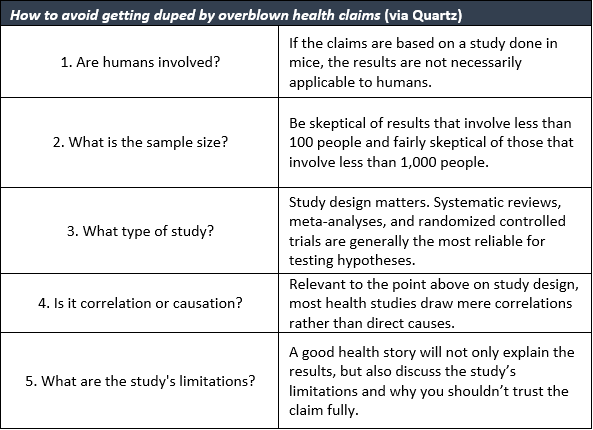

In addition to poor quality research, bad reporting further complicates the issue. As Bohannon notes, reporters covering topics such as nutrition or broader scientific research should not merely echo what they read in press releases: you have to know how to read a scientific paper and actually bother to do it. Readers should be especially weary of articles that do not mention sample size and effect size (see Table below for specific tips).

Bohannan is not alone in his views. Lancet editor Richard Horton recently published a commentary on bad scientific practices, claiming that much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue. Increased public awareness and transparency are likely to ameliorate the problem. In the meantime, both reporters and readers should be cautious as they digest health headlines if it sounds too good to be true, it likely is.

Table content via Quartz (http://qz.com/462050/how-to-avoid-getting-duped-by-overblown-health-claims/)

Table content via Quartz (http://qz.com/462050/how-to-avoid-getting-duped-by-overblown-health-claims/)

Have any recent headlines caught your attention (like the one about a glass of wine being as good as going to the gym)? Let us know by sharing in the comments below or tweeting at either @VitalityInst or at Sarah Kunkle @Sareve.